Generative Frameworks for Robot Imitation Learning

Generative models have the ability to induce probability distributions from large unstructured datasets to produce new data samples that, in theory, just seem to have come from the original unknown data distribution. To achieve this, generative models minimise the divergence between the data and learnt distributions. Similarly to generative models, imitation learning (IL) also aims to minimise the diverge between two probability distributions. In the case of IL, these are distributions of the agent’s and the expert’s motions. Viewing the demonstration motions as i.i.d samples from the expert (data) distribution, it follows that the underlying objectives of imitation learning are essentially the same as those of generative modelling [Osa, et al. (2018)]. The only distinction is that unlike generative modelling, where the goal is to just return new samples, the goal with imitation learning is to instead learn a policy that maps an agent’s state to some desired action. Given the aligned objectives of these methods, it stands to reason that their combination might lead to newer techniques that benefit from their individual merits. The key idea with generative imitation learning is to leverage the many advantages of generative objectives (sample diversity, better expressiveness etc.) to better guide an agent towards the intended policy.

In usual circumstances, the probability distributions learnt by generative models are not their direct output and are just used to sample the new data points that the model returns as outputs. While different generative techniques model the distributions differently (EBMs use energy functions while GANs use classifiers to iteratively update a sampling function), in all cases of generative modelling, the probability distributions inherently specify the desirability of the generated sample. The higher the probability of a sample, the more likely it is that this sample might have come from the data distribution. In the case where the data points are the expert’s motions, the learnt probability distribution can be leveraged as cost functions that might drive a learning agent to take desirable actions. Hence, using generative objectives to learn reward functions, a learning algorithm could easily distil the motivations of the expert and the dynamics of the environment just from demonstrations, while having the added benefit of generating diverse samples. In this post, we will briefly look at a few popular generative IL algorithms and identify some of their benefits and limitations.

Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL)

[Ho, and Ermon, (2016)] introduce GAIL, a method to iteratively learn and optimise the return from the underlying reward function implied in expert demonstrations through an optimisation objective similar to that seen in Generative Adversarial Networks [Goodfellow, et al. (2020)]. GAIL proposes to “directly” learn a policy instead of first learning a reward function and then optimising it (although internally it still does learn a reward function). While much of the theoretical work discussed in [Ho, and Ermon, (2016)] is beyond the scope of this post, the main theoretical contributions are described below.

In general, IRL can be formulated as a procedure which finds a reward function under which the expert outperforms all other policies. Note that this does not directly imply that the expert’s policy is optimal at solving the problem but instead defines IRL as a problem where a reward function is found under which the expert policy is the best. In this formulation, the reward function is defined to be regularised by a function \(\psi\). An RL problem can then be defined to optimise the reward function returned by the inner IRL problem. [Ho, and Ermon, (2016)] provide a different perspective on IRL by first defining a policy in terms of its occupancy measure \(\rho_{\pi}\) – the distribution of state-action pairs that an agent encounters when navigating the environment with the policy – and then viewing IRL as a procedure that tries to induce a policy that matches the expert’s occupancy measure. In doing so they show that various settings of \(\psi\) lead to various imitation learning algorithms with varying degrees of similarity between the expert and the imitator. With no reward regularisation, one can theoretically recover a policy that exactly matches the expert’s occupancy measure. While this is enticing at first, it is not very practical as the expert dataset is finite and can not cover all possible ways of acting in a very large state-action space. They then show various examples of regularisation and its effect on the ability of the recovered policy to match the expert’s occupancy measure.

Under this interpretation of IRL, [Ho, and Ermon, (2016)] propose a new form of regularisation \(\psi\) under which the imitator policy accurately matches the expert’s occupancy measure while also being tractable in large environments. The regulariser from GAIL is

\[\psi_{GA} = \begin{cases} \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{E}} [g(r(s,a))] & \text{if } r<0 \\ +\infty & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]where $r(s,a)$ is the cost function learnt via IRL and

\[g(x) = \begin{cases} -x - \log(1 - e^x) & \text{if } x<0 \\ +\infty & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]This regulariser places low penalties on reward functions that return high rewards to expert state-action pairs and heavily penalises those that assign low rewards to the expert. \(\psi_{GA}\) is also dependent on the expert dataset and is hence problem agnostic. Based on this definition, \(\psi_{GA}(\rho_{\pi} - \rho_{\pi_E})\) equates to the Jensen Shannon divergence between \(\rho_{\pi}, \rho_{\pi_E}\). Minimising \(\psi_{GA}\) is roughly equivalent to minimising the difference between the imitator and expert. This interpretation of the regulariser is analogous to generative adversarial networks where a generator network \(G\) attempts to generate samples that “fool” a discriminatory \(D\). In the case of GAIL, the learner’s occupancy measure \(\rho_{\pi}\) is analogous to the distribution of the generator while the true data distribution is represented by the expert’s occupancy measure \(\rho_{\pi_E}\). GAIL essentially boils down to learning a discriminator (classifier) to distinguish between these two and finding a saddle point as a policy that minimises the classification error. The GAIL optimisation problem is

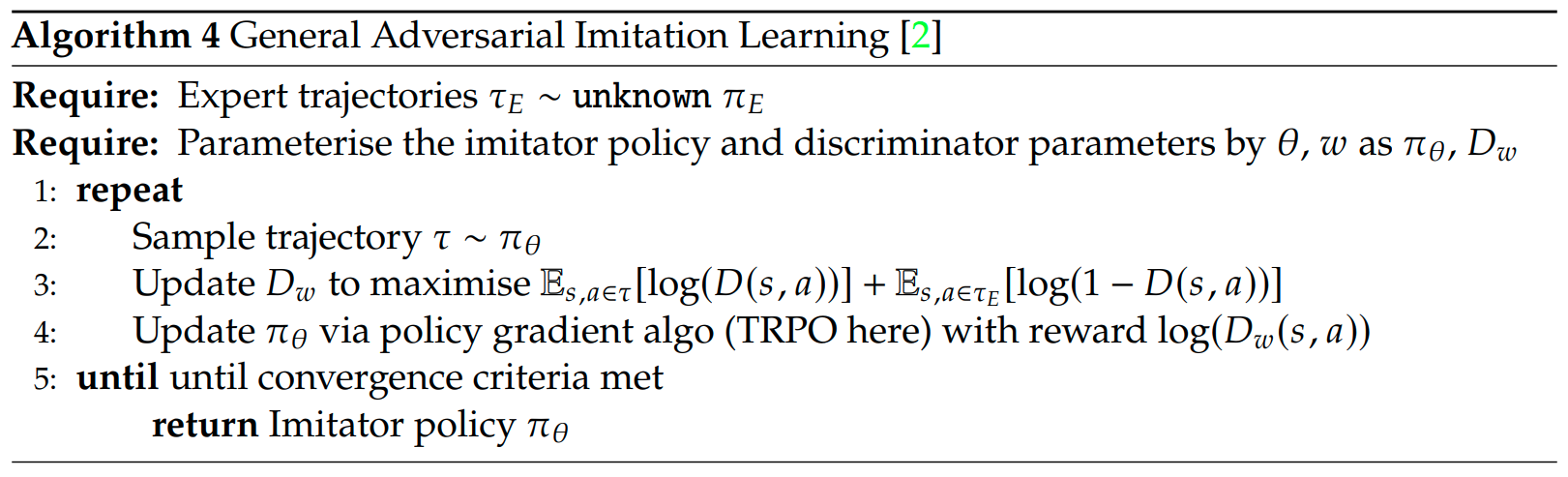

\[\begin{align*} \min_{\pi \in \Pi} \; \max_{D \in (0,1)} \; \mathbb{E}_{s,a \sim \pi} [\log(D(s,a))] + \mathbb{E}_{s,a \sim \pi_E} [\log(1 - D(s,a))] \end{align*}\]Intuitively GAIL simply uses the learnt discriminator as an implicit “reward” function and iterates between using RL to update the policy and updating the discriminator parameters by maximising the difference between the distributions of the expert and imitator trajectories.

GAIL pseudocode.

Adversarial Motion Priors

Adversarial motion priors [Peng, et al. (2021)] is an imitation learning algorithm that combines goal-conditioned reinforcement learning with a GAIL style reward function learning scheme modified for state-only settings. AMP is built on the idea that while it is quite challenging to assign an objective for the “style” of motion that the imitator is supposed to learn, it is still straightforward to define higher-level objective functions like symmetry and effort. AMP learns this style reward by learning to discriminate (classify) motions in the expert’s dataset from those executed by the learner’s policy. Similarly to other adversarial imitation learning methods, AMP then trains the imitator via reinforcement learning using the classifier’s output as a reward function.

The key contributions of AMP are the incorporation of goal-conditioned RL within state-only adversarial imitation learning and the excellent empirical results shown on full-body humanoid motion imitation. Since AMP only uses reference motions (and not actual actions) executed by the expert, the style-reward learnt can also be generalised across different agent embodiments. In doing so, AMP also sidesteps the embodiment correspondence issue.

Formally, AMP uses a linear combination of task reward \(r^G(s, s', a, \text{goal})\) and a style-reward \(r^S(s, s')\) that is learnt as a discriminator \(D(s,s')\) learnt through a modified GAIfO objective.

\[\begin{align*} r(s,s',a,g) &= w^G r^G(s, s', a, \text{goal}) + w^S r^S(s, s') \\ r^S(s, s') &= \max [0, 1-0.25(D(s,s') - 1)^2] \end{align*}\]The offset, scaling, and clipping are done to bind the learnt reward function between \([0,1]\) as the author’s claim that this aids training. The discriminator is learnt by slightly modifying the GAIL objective function to match the least squares GAN objective. This is done to simplify the optimisation challenges that are typically seen in GAN-like training. The discriminator objective in AMP is shown below. Proximal policy optimisation is used within the algorithm to learn the final policy.

\[\begin{align*} \arg \min_D \mathbb{E}_{s,s' \sim \tau_E} [(D(s,s') - 1)^2] + \mathbb{E}_{s,s' \sim \tau_{\pi}} [(D(s,s') + 1)^2] \end{align*}\]Diffusion Policy

Diffusion policy [Chi, et al. (2023)] employs a procedure to directly learn a mapping from states to actions as a conditional denoising diffusion process (DDPM [Ho, et al. (2020)]). In doing so, they learn a policy in a behaviour cloning-like fashion (by matching the expert demonstration and policy distributions) but also maintain the generalisation capabilities of diffusion models. They propose to make two main modifications to DDPM that enable its use in robotics problems with visual state information. First, the data modality from DDPM is changed from images to robot action trajectories. Second, the denoising process is conditioned on the visual state information.

The diffusion model is trained to predict temporally consistent, and reactive sequences of actions while the predicted actions are applied in the environment via receding horizon control. Concretely, at every timestep \(t\), the diffusion model takes in the previous \(T_o\) timesteps of observations \(O_t\) and returns a sequence of actions of size \(T_p\). From this sequence, the first \(T_a\) actions are actually applied to the environment. [Chi, et al. (2023)] claim that the use of sequences of observations and the application of the receding horizon principle encourages temporal consistency in actions as the next set of actions is always conditioned on the previous observation sequence. The conditioning of model outputs is naturally facilitated by diffusion models and the FiLM [Perez, et al. (2018)] layer is used to compute conditioned latent space samples of inputs from which the model learns \(p(a_t \vert O_t)\). Once a diffusion model is trained, action sequences are generated by \(K\) steps of inference at each environment timestep \(t\). The denoising update at each inference step is

\[\begin{align*} a_{t}^{k-1} = \alpha (a_{t}^{k} - \gamma \epsilon_{\theta}(O_t, a_{t}^{k}, k) + \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2 I)) \end{align*}\]The paper presents varied experiments on both real and simulated environments to show that diffusion policy can learn multimodal action distributions better than other state-of-the-art methods, and is capable oh high-dimensional representation learning (predicting sequences of actions rather than single actions). They also show detailed comparisons of neural network architectures like CNNs and Transformers and propose general guidelines for visual encoder modelling. Diffusion policy is compared against Implicit Behaviour Cloning, a general procedure to learn an energy function and then minimise this via a variety of procedures. Being an EBM, implicit behaviour cloning in theory must also possess the same advantages as diffusion. However, through empirical results, comparisons of learning curves, and theoretical argumentation, [Chi, et al. (2023)] show that using diffusion models leads to substantially more stable training than IBC. They argue that the main reason for the stability of diffusion policy is because diffusion models avoid the computation of the normalisation constant \(Z_{\theta}\) – something that the energy-based training of IBC approximates through a sampling process.

Summary & Overall Limitations

Before diving into a detailed technical analysis of these algorithms, it is important to first identify the desired features of an imitation learning algorithm. The ideal generative modelling based IL algorithm

- Has stable training characteristics

- Is capable of learning diverse, multi-modal expert distributions or a policy that depicts multi-modal behaviour

- Is admissible to the process of conditioning (thereby allowing some flexibility over the features of the generated motion)

- Learns a smooth distribution that can provide informative gradients at all points in the sample space

- Operates with partially observable demonstrations

Algorithms like GAIL, Generative Adversarial Imitation from Observation (GAIfO), Conditional Adversarial Latent Models (CALM), and AMP have shown markedly good empirical performance. It can be argued that Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP) is the best from this set because of the combination of learnt “style” rewards with goal-conditioned RL rewards obtained from the environment. This allows the agent to mimic the style of the expert motion while still separately optimising the goals implied by the environment’s reward function. In comparison to CALM, which also uses a very similar procedure, AMP is arguably better as it does not need to learn two independent policies which are then connected by another user-configured finite state machine. Finally, AMP also uses state-only demonstrations and is hence easier to apply in the real world.

Unfortunately, most of the GAN-derived algorithms (including AMP) fail to satisfy the requirements discussed above. The simultaneous min-max optimisation in these algorithms has been studied in detail in several past studies [Arjovsky, and Bottou (2017), Saxena, et. al (2021)] and is known to be quite unstable. The policy (generator) update in these algorithms suffers further instability as it requires the estimation of the performance measure by the computation of an expectation over complete trajectories – a high-variance process due to the inherent stochasticity of environments and the inability of the expert dataset to cover all possible trajectories in the trajectory space. The GAN-like optimisation objective also suffers from issues like mode-dropping that render the learnt distributions inadequate at generating diverse samples. It is further inadmissible to conditioning. When used as a reward function, the non-smooth discriminator also fails to provide informative gradients from which a policy could be learnt. GAIL and similar techniques also require the actions taken by the expert and are restricted in their practical applicability.

In contrast, the energy-based density estimation in algorithms like Diffusion Policy sidesteps the issues of instability and restricted output modality. It is also naturally admissible to conditioning on features that affect sample characteristics. More importantly, energy functions are smooth in the sample space. When used as reward functions they can provide informative gradients based on which a policy can be optimised. It is important to highlight that although Diffusion Policy uses complete trajectories of expert demonstrations (and subsequently also predicts a sequence of actions), it is not prone to instability arising from the variance in trajectories. This is because Diffusion Policy is a one-shot approach and does not involve subsequent reinforcement learning in the loop to optimise a policy.

However, Diffusion Policy and its alternatives require the expert’s actions and are somewhat restricted in their practical applicability. Diffusion Policy can also be seen as a generative version of behaviour cloning as it aims to directly capture the distribution of expert trajectories and produces action sequences as a function of observation history (conditioning the diffusion process on observations). Under this interpretation, it can be argued that Diffusion Policy also suffers from the correspondence problem. Even though diffusion can generate diverse samples and the receding horizon control used in Diffusion Policy ensures some degree of temporal consistency, Diffusion Policy might still fail to reliably replicate the expert. The main challenge might be to learn corrective behaviour once the agent has already slightly deviated from the trajectory recommended by the expert policy. This could be worsened if the demonstration distribution is not the same as the distribution of trajectories encountered by the agent.

From this, it appears that there is a mixed set of benefits and drawbacks to these methods and a single algorithm cannot claim to dominate others. A combination of the beneficial features of these techniques might lead to a better imitation learning algorithm that does supersede the current state-of-the-art.

References

Content derived from the related literature to my MSc. thesis.

Osa, Takayuki and Pajarinen, Joni and Neumann, Gerhard and Bagnell, J Andrew and Abbeel, Pieter and Peters, Jan and others (2018). An algorithmic perspective on imitation learning. Foundations and Trends{\textregistered} in Robotics

Ho, Jonathan and Ermon, Stefano (2016). Generative adversarial imitation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems

Goodfellow, Ian and Pouget-Abadie, Jean and Mirza, Mehdi and Xu, Bing and Warde-Farley, David and Ozair, Sherjil and Courville, Aaron and Bengio, Yoshua (2020). Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM

Peng, Xue Bin and Ma, Ze and Abbeel, Pieter and Levine, Sergey and Kanazawa, Angjoo (2021). Amp: Adversarial motion priors for stylized physics-based character control. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG)

Chi, Cheng and Xu, Zhenjia and Feng, Siyuan and Cousineau, Eric and Du, Yilun and Burchfiel, Benjamin and Tedrake, Russ and Song, Shuran (2023). Diffusion policy: Visuomotor policy learning via action diffusion. The International Journal of Robotics Research

Ho, Jonathan and Jain, Ajay and Abbeel, Pieter (2020). Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems

Perez, Ethan and Strub, Florian and De Vries, Harm and Dumoulin, Vincent and Courville, Aaron (2018). Film: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer.

Saxena, Divya and Cao, Jiannong (2021). Generative adversarial networks (GANs) challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR)

Arjovsky, Martin and Bottou, L{'e}on (2017). Towards principled methods for training generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.04862